In anticipation of the first Peanuts full-length movie in thirty-five years, there have been a spate of articles dealing with the iconic comic strip drawn by Charles M. Shulz that began to appear in newspapers in October 1950. My attention was drawn in particular to Aaron R. Katz’ essay in Tablet, entitled “The Wisdom of Peanuts” ( http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-life-and-religion/194546/twerski-charlie-brown ) in which he interviews R. Abraham Twerski, the well-known, prolific, deeply observant and knowledgeable psychiatrist and addiction specialist, who not only wrote a number of books mining psychological insights from Peanuts, but who, it turns out, had a personal relationship with Shulz until the animator’s death.

R. Twerski recounts to Katz that during their first meeting, recognizing R. Twerski’s background and religious orientation, Shulz asked him a theological question, the classical quandary of “Why do good things happen to bad people?” (It is interesting that R. Twerski does not remember that the question included the converse, i.e., “and bad things to good people.”) Katz quotes R. Twerski’s response to the query as follows:

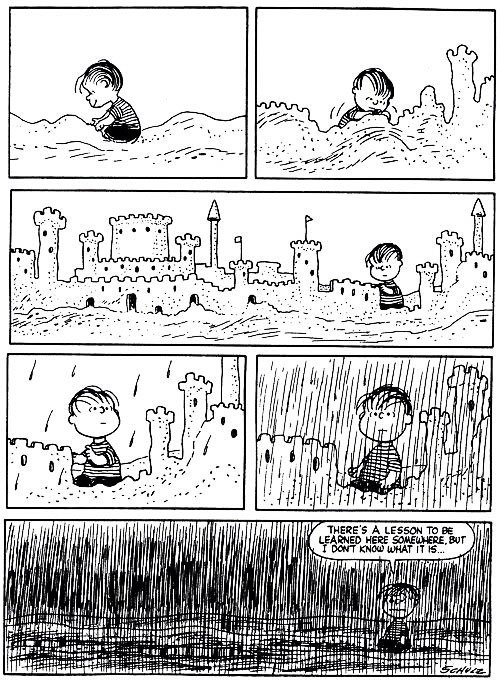

Twerski responded by reminding Shulz of a Peanuts strip from 1959. In it Linus is seen laboring to build a very intricate sand castle. Suddenly it begins to drizzle and before long, the sand castle is wiped away by the torrential rain. Linus then says to himself, “There is a lesson to be learned here somewhere, but I don’t know what it is…” Twerski, despite being well-versed in matters of Jewish theology, admitted that he found Linus’ statement to be a profound response to the age-old question.

Below is the comic strip which was included in Katz’ essay and to which R. Twerski referred:

Aside from the fact that using comic strips in order to convey psychological truths and even theological ideas is an extremely non-threatening format by which individuals who otherwise may be adverse to taking such matters seriously, can be exposed to concepts that can readily be applied to myriad personal situations and experiences, I think that this becomes a parable for how all forms of culture, both “high” and “low,” can serve as catalysts for deep reflection and addressing the various aspects of the human condition in which we find ourselves. It is important therefore that parents and teachers regularly model for their children and students the manner in which all literature, drama, music, sports, etc. can be processed–not necessarily exclusively, since the sheer pleasures that such experiences can offer should also be appreciated—in order that a young individual’s social, intellectual and emotional development be encouraged and strengthened. Ironically, religious experiences, which potentially should offer the greatest number of and most profound opportunities for such reflection, are often reduced to mechanical ritual, bland truisms, and non-empathic prejudices and judgments.

But returning to the specific issue at hand, i.e., theodicy, Linus’ observation that while life continually teaches lessons, human beings have difficulty discerning them, is profound in and of itself. Theodicy clearly is the great problem for all religious systems—if God Exists, why aren’t there readily apparent, logical causes and effects in the world which He Created and in which we spend our lives? On the one hand, some people do not do well with mystery and open-ended questions. They prefer to engage in activities that lend themselves to clear resolution and easy evaluation. If they become aware that certain of their efforts might well come to naught, sooner or later– the intrinsic nature of sand-castles is such a wonderful metaphor for so much of human behavior, because even if it doesn’t rain, sand is intrinsically unstable, the tide will eventually come in, or someone will come along and kick down what someone else so carefully assembled—they will decide that it is not worth it for them to even engage, and prefer instead to do something else, or nothing at all. I think that a more realistic attitude that reflects more appropriately the human condition is described by R. J.B. Soloveitchik, Z”L, in his essays, “Catharsis” (http://traditionarchive.org/news/originals/Volume%2017/No.%202/Catharsis.pdf ) and “Majesty and Humility” (http://traditionarchive.org/news/originals/Volume%2017/No.%202/Majesty%20and%20Humility.pdf ) that first appeared in Tradition Spring 1978, 17:2. The Rav notes that even as man is able to assert himself and feel victorious at certain points of his life, he must also be able to accept limitations vis-à-vis his personal abilities as well as what he is permitted to do and not do according to Halacha. Then there are others who optimistically, self-confidently and self-absorbedly plunge ahead, believing that everything will finally become clear at some point and success is only around the corner, but then become embittered when their dreams are not realized in a manner that is concomitant to their expectations.

An alternative position might be that we must try to believe that things ultimately make sense from HaShem’s Perspective, as was recounted so eloquently to Iyov at the end of the book; however we simply cannot expect to ever truly understand how and/or why. The best we can do is try our best and live lives as redeemed and just as possible, weathering the figurative “rain squalls” to the best of our abilities, as we assume Linus does, and simply try to rebuild, even in a Sisyphusian manner, should our “sand-castles” become undone, as they inevitably will.

You must be logged in to post a comment.